Indians clash with farmers over ancestral lands - CNN.com

Indians clash with farmers over ancestral lands - CNN.com

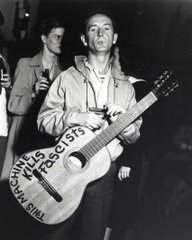

DOURADOS, Brazil (Reuters) -- When Carlito de Oliveira returned to the ancestral lands he was forced to abandon 50 years ago in southwestern Brazil, he found the forest had been turned to pasture land.

But the Kaiowa Indian refused to give in. He invaded the ranch with his family in 2001, and has held on despite repeated clashes with police and gunmen.

"This is where my grandfather is buried; I give my life for this land," Oliveira said at the camp outside the farming frontier town of Dourados.

Like Oliveira and his family, more and more of the some 40,000 Indians in this area are abandoning overcrowded reserves where alcohol and drug abuse are widespread to reclaim the land they once inhabited.

Facing overt racism and with little or no political power to improve their plight, their traditional submissiveness is giving way to growing anger.

"They're not going to die like some endangered species without putting up a fight," says Zelik Trajber, chief physician in the nearby Dourados reservation. "If they could organize, they'd be a serious problem."

Already, the struggle is fueling rural violence in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul and worries farmers.

"They are destabilizing Brazil's agriculture, they are the biggest threat to our production," said Gino Ferreira, head of the Dourados farmers' association. His father is one of the pioneers who settled the area decades ago.

Ferreira said he would mobilize farmers to defend their property if Indians continued to occupy land.

Driven away

After a sign from a guard at the entrance to his camp that all was safe, Oliveira emerged from hiding to tell how his family was driven from the land in 1957, when he was 17 years old.

"Settlers said we had to leave because they were now the owners -- we walked for three days to the reservation," he said. "How could the government sell something that was ours without asking us?"

Since two policemen were shot dead during a skirmish at the camp a year ago, Oliveira and about 50 members of his extended family do not go into town for fear of reprisal.

They lack medicines and other basic goods.

In the camp's bare school, five young students rehearsing Kaiowa pronunciation light up at the sight of a bar of soap a public official brought during a recent visit.

A sign on the wall reflects what many Indians here think: "How to live in a country in which we were first and now are one of the last."

Wary of death threats by gunmen who have repeatedly invaded the camp and fired shots, Oliveira breaks into tears as he tells how police dragged most of the camp's men to prison after the policemen were shot.

A federal court in 2004 granted Oliveira's family the right to remain on the farm until government anthropologists decide on the validity of its claims.

Even with their ancestral land-rights established, many Indians see their claims stalled in a judicial tangle. Farmers often challenge rulings that give land back to Indians because the government does not compensate them for their losses.

President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva's left-leaning government has spent billions of dollars, however, to settle landless peasants, who exert more pressure on politicians and government officials in the capital.

Rosangela Carvalho, who heads a government task force set up last month to look at the crisis of Indian tribes in the region, says politics is the problem.

"The biggest obstacle to solving the Indian issue is the ignorance and red tape in Brasilia."

No comments:

Post a Comment